WRITING FOR TRUMPET 201

ADVANCED TIPS FOR COMPOSERS

|

I wanted to share a few thoughts and point out some of the common mistakes I often encounter while working with composers who still haven’t had enough experience writing for brass instruments. There isn’t going to be a “Writing for trumpet 101”, since there are already some very thorough resources available out there that cover most of the basics, so there’s no point in me repeating the same things, only to a much smaller audience. I can warmly recommend the book “Modern Times For Brass” (conveniently printed in both german and english). Here is a free sample where you can find about one-third of the book. Or, if the money is tight, here and here are some useful free online resources.

Anyway, let’s dig right in, with one the most common misconceptions: 1. HALF-AIR HALF-SOUND To put it plainly: there is no such a thing. A flute can do this, but a brass instrument operates more like an on/off switch. The reason for this is that we have a default position of the mouth called the embouchure which is automatically set to vibrate and produce a pitched sound; if we intend to play the air-sound, we need to significantly alter that position in order to prevent a pitched sound (the vibration) from accidentally happening. This is what I mean by the on/off switch, it’s either an air-sound (no lip vibration) or a regular sound. |

That being said, there are various other things we can do to “corrupt” the regular sound and reach a similar effect, but by definition none of these should be classified (and notated) as air-sounds or “half-air-sounds” because that’s not what they are (the German term for air-sound is even more accurate: “tonlos”; or “toneless” in English, which makes it look all the more absurd when something is notated as “half-toneless”)

Depending on the context you might want to consider one or more of the following three techniques to achieve something close to what you may have imagined:

“Sub-tone” is a kind of high wind-low vibration technique, producing an airy timbre which is used a lot in jazz music (even the most casual music listeners will probably be familiar with the trumpet sound of Chet Baker).

“Buzz”: by slightly releasing the mouthpiece pressure, we can allow the lip buzzing sound to “leak out” while producing a sound

“Ghost tones”: sharp attacks or sustained tones in the softer-than-possible dynamic, where you only hear the hint of the pitch, although it never fully develops; this takes some practice and might not always work 100% unless the player’s lips are in a particularly refreshed state on that day (which is always a bit of a lottery).

Sub-tone and ghost tones do require a bit of skill and preparation, but every trumpet player will at least be able to produce some sort of buzz leak, which is also by far the most versatile effect of the three, as it works well with every type of articulation (ghost tones work better detached, while the sub-tone is more useful in legato)

Depending on the context you might want to consider one or more of the following three techniques to achieve something close to what you may have imagined:

“Sub-tone” is a kind of high wind-low vibration technique, producing an airy timbre which is used a lot in jazz music (even the most casual music listeners will probably be familiar with the trumpet sound of Chet Baker).

“Buzz”: by slightly releasing the mouthpiece pressure, we can allow the lip buzzing sound to “leak out” while producing a sound

“Ghost tones”: sharp attacks or sustained tones in the softer-than-possible dynamic, where you only hear the hint of the pitch, although it never fully develops; this takes some practice and might not always work 100% unless the player’s lips are in a particularly refreshed state on that day (which is always a bit of a lottery).

Sub-tone and ghost tones do require a bit of skill and preparation, but every trumpet player will at least be able to produce some sort of buzz leak, which is also by far the most versatile effect of the three, as it works well with every type of articulation (ghost tones work better detached, while the sub-tone is more useful in legato)

2: DON'T BE AFRAID OF OUR VOLUME

This is another issue I often encounter: in most ensemble pieces which are generally supposed to sound low-volume or delicate, the only trumpet sounds used will be harmon-mute or air sounds.

If you want to give fuel to all the haters saying things like “contemporary music is dead”, and “every piece since Darmstadt sounds the same anyway”; this way of scoring for trumpet will be a very good way to go about it.

Still, in most cases young composers will not choose these overused colors because they think they still sound “cool” or interesting; but simply out of fear that anything else will be too present and ruin the balance. I found this fear to be greatly exaggerated, as there is a wide variety of nice sounds you can make in the low volume, especially in the middle register of the instrument.

One thing you might particularly want to avoid is mixing these two together and using air sounds while the harmon-mute is on (or any mute, for that matter). This is not only an overkill in terms of volume, but it also simply doesn’t sound very good, as the air sounds need the resonance of the open bell to develop their “body”

Both harmon-mute and air sounds have a very narrow dynamic range (approximately ppp to mp in the perceived dynamic), so we’ll often encounter an opposite problem - as soon as the general dynamic grows even slightly, the trumpet will just disappear from the mix. Similarly, if you have the whole brass section play the air sounds at the same time, the lower brass will have a much bigger volume for obvious reasons; so the trumpet (and the french horn) might not be able to compete.

Also, keep in mind that it’s much easier to incorporate a mute during the rehearsal process, then it is to disregard it: If a conductor notices a balance problem which can’t be solved otherwise, it’s a very easy decision for them to fix the issue with some mutes. On the other hand, if a trumpet is inaudible, and you wrote for a harmon-mute, most conductors will assume you wanted that specific timbre and will be reluctant to make a change, especially if you’re not present in the rehearsal.

This is another issue I often encounter: in most ensemble pieces which are generally supposed to sound low-volume or delicate, the only trumpet sounds used will be harmon-mute or air sounds.

If you want to give fuel to all the haters saying things like “contemporary music is dead”, and “every piece since Darmstadt sounds the same anyway”; this way of scoring for trumpet will be a very good way to go about it.

Still, in most cases young composers will not choose these overused colors because they think they still sound “cool” or interesting; but simply out of fear that anything else will be too present and ruin the balance. I found this fear to be greatly exaggerated, as there is a wide variety of nice sounds you can make in the low volume, especially in the middle register of the instrument.

One thing you might particularly want to avoid is mixing these two together and using air sounds while the harmon-mute is on (or any mute, for that matter). This is not only an overkill in terms of volume, but it also simply doesn’t sound very good, as the air sounds need the resonance of the open bell to develop their “body”

Both harmon-mute and air sounds have a very narrow dynamic range (approximately ppp to mp in the perceived dynamic), so we’ll often encounter an opposite problem - as soon as the general dynamic grows even slightly, the trumpet will just disappear from the mix. Similarly, if you have the whole brass section play the air sounds at the same time, the lower brass will have a much bigger volume for obvious reasons; so the trumpet (and the french horn) might not be able to compete.

Also, keep in mind that it’s much easier to incorporate a mute during the rehearsal process, then it is to disregard it: If a conductor notices a balance problem which can’t be solved otherwise, it’s a very easy decision for them to fix the issue with some mutes. On the other hand, if a trumpet is inaudible, and you wrote for a harmon-mute, most conductors will assume you wanted that specific timbre and will be reluctant to make a change, especially if you’re not present in the rehearsal.

3: WHEN (NOT) TO NOTATE THE FINGERINGS

It is great that you took your time to learn the fingering tables. This is a vital part of understanding how a brass instrument works, and will help you a lot knowing which glissandi (also valve-tremolos, microtones…) are possible and which aren’t. Sometimes the young composers are so proud of this newly acquired knowledge that they have a tendency to “spam” the fingerings throughout the trumpet part, which isn’t necessary and tends to make the score cluttered and less readable.

There is however one notable exception to this: if you are looking for microtonal deviations based on the natural harmonic scale (most notably the seventh partial being 31 cents lower); in this case it is indeed helpful if you simply write the alternative fingering instead of the -31 cents marking above the note. (like the A above the staff being played with “2” instead of “1&2” resulting in the 7th harmonic in the series over B natural)

Trumpeters playing modern instruments are generally not used to thinking in cents; so if there’s another more organic way of notating your natural overtones (such as fingerings or even simple arrows) it is always welcome.

It is great that you took your time to learn the fingering tables. This is a vital part of understanding how a brass instrument works, and will help you a lot knowing which glissandi (also valve-tremolos, microtones…) are possible and which aren’t. Sometimes the young composers are so proud of this newly acquired knowledge that they have a tendency to “spam” the fingerings throughout the trumpet part, which isn’t necessary and tends to make the score cluttered and less readable.

There is however one notable exception to this: if you are looking for microtonal deviations based on the natural harmonic scale (most notably the seventh partial being 31 cents lower); in this case it is indeed helpful if you simply write the alternative fingering instead of the -31 cents marking above the note. (like the A above the staff being played with “2” instead of “1&2” resulting in the 7th harmonic in the series over B natural)

Trumpeters playing modern instruments are generally not used to thinking in cents; so if there’s another more organic way of notating your natural overtones (such as fingerings or even simple arrows) it is always welcome.

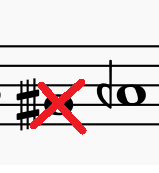

4: MINIMIZE THE "HASHTAGS"

|

Quarter-tones on brass instruments are always produced by lowering the pitch, so we are always thinking from the higher note; for example, if I want to play a quarter tone between G♯ and A, I am starting from the A position, and then extending the pipe to lower the pitch (either by pulling out the slide, or by pressing a specially built quarter tone valve, if I happen to have one of those).

Therefore it would make it much faster to read if you could think of these enharmonic adjustments wherever possible and write the quarter-tones as a lowering of the higher note (in the above example, you would notate the lower A instead of the higher G♯) , the players would appreciate it very much. Even in those rare occasions where we have no way of extending the pipe and have to resort to lip-bends, we would still play the upper note and bend downwards; so we're still lowering the pitch (this occurs when the only valve position available for the upper note is either open or 2nd valve only; on the trumpet this happens on the low C and B). The two examples on the right might clarify what I mean: in the bottom picture we're either lowering the G♯ or the Ab, both of which are common notes, so our brain will automatically "command" the needed fingering (2nd and 3rd valve for G♯/A with the 3rd valve pulled out to lower the pitch). On the top picture we are lowering the G♯♯ or A - with G♯♯ being a relatively uncommon note, so our brain will always need an extra split second to "convert" it into the A first, and then think about the fingering. |

|

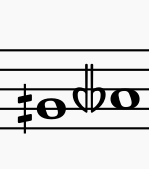

Just another general remark about the quarter-tones: they are all perfectly possible to do on a normal trumpet (without the specially built quarter-tone valve). However, some fingerings are more awkward than others, so it would be smart to avoid those pitches in a faster tempo. Some of the actions which slow us down include lip bends; having to pull the 3rd valve slide more than a half-way out (we usually have to do this when lowering the 7th position, which is naturally too sharp in every register except the lowest) and also doing literally anything involving the 1st valve slide (unless we have a trigger system built in, which most newer models don't). To help illustrate what I'm talking about, we should take a look at a quarter-tone fingering chart. Since I wasn't able to find one online, you will have to tolerate this one I made myself (using my Photoshop skills of a 5-year-old child). I used only the flats, to get you used to it.

The notes in red are the awkward ones, and the yellow ones are "slightly awkward".

+ the valve slide is pulled out to a varying degree

⤵ lip bend

(notice that the lip bends in the higher register aren't colored as "awkward", as they are just small pitch corrections, as opposed to the full quarter-tone bends we need for those two low notes)

+ the valve slide is pulled out to a varying degree

⤵ lip bend

(notice that the lip bends in the higher register aren't colored as "awkward", as they are just small pitch corrections, as opposed to the full quarter-tone bends we need for those two low notes)

5: Bb OR C TRUMPET?

This is another matter that tends to be a little confusing to the composers. Long story short: Bb and C trumpet are actually rather similar in both range and timbre. The Bb trumpet is commonly understood to sound more “dark” or “jazzy”, while the C trumpet is supposedly more “brilliant” or “bright”. I wouldn’t say this is a total myth and there is some truth to it, but in reality there are countless other factors which will strongly influence the timbre of both of these instruments; the choice of mouthpiece plays a big role, so does the breathing technique and even the physiology of the player. And yes, someone can actually have a larger and darker sound on the C trumpet than someone else has on the Bb.

So, unless you are writing either a solo piece or an ensemble piece where the trumpet is featured in a significant role, the timbre difference will be almost impossible to notice even for an experienced trumpet player, let alone for the general audience. And If the trumpet is muted, it practically won’t matter at all, even as a solo.

Ok, then, for all the situations where it doesn’t matter: what would be the “default” trumpet to use? There was actually a bit of a war going on over this historically, with the C trumpet being pushed mostly by the French, while the Bb trumpet was favored in the anglophone countries and Russia (the Germans kind of sat this one out as they are more involved with a different battle: rotary vs. piston valves). Anyway, at some point the C trumpet did actually establish itself as a de facto “default” instrument to use in contemporary ensemble music. So if you are writing a piece which will be performed along with other works in a concert , chances are that the trumpet player will already have their C trumpet there.

Moving on to the range. As you probably already know, there is a small difference: the lowest note on a C trumpet without bending or pedals will be the low F♯ (or F natural, if we stretch the 3rd valve slide all the way out); whereas the Bb trumpet will go a whole tone lower (E/Eb), so if those two additional notes mean a lot to your piece, that would be one of the valid reasons to opt for the Bb trumpet. Consequently there is also a difference in the ranges of possible harmonic series (for split-tones, air-sounds etc.). The C trumpet will NOT have the harmonic series over C♯, D, Eb and E; with the Bb trumpet you will gain Eb and E while losing C and B. So this might be something to keep in mind for all the spectralists and post-spectralists out there. Every harmonic series on a same instrument would only be possible with the 4th-valve, however those are unfortunately rarely used these days.

As for the high register, the C trumpet doesn’t go any higher than the Bb, but it might be more precise (less prone to missed notes), especially in the upper part of the second octave, and around the concert high C. Above the high C it doesn’t matter very much; if you aim for precision in that register, you’re better off with the piccolo trumpet (which BTW also doesn’t go any higher than the large trumpets; but the improvement in precision is significant)

This is another matter that tends to be a little confusing to the composers. Long story short: Bb and C trumpet are actually rather similar in both range and timbre. The Bb trumpet is commonly understood to sound more “dark” or “jazzy”, while the C trumpet is supposedly more “brilliant” or “bright”. I wouldn’t say this is a total myth and there is some truth to it, but in reality there are countless other factors which will strongly influence the timbre of both of these instruments; the choice of mouthpiece plays a big role, so does the breathing technique and even the physiology of the player. And yes, someone can actually have a larger and darker sound on the C trumpet than someone else has on the Bb.

So, unless you are writing either a solo piece or an ensemble piece where the trumpet is featured in a significant role, the timbre difference will be almost impossible to notice even for an experienced trumpet player, let alone for the general audience. And If the trumpet is muted, it practically won’t matter at all, even as a solo.

Ok, then, for all the situations where it doesn’t matter: what would be the “default” trumpet to use? There was actually a bit of a war going on over this historically, with the C trumpet being pushed mostly by the French, while the Bb trumpet was favored in the anglophone countries and Russia (the Germans kind of sat this one out as they are more involved with a different battle: rotary vs. piston valves). Anyway, at some point the C trumpet did actually establish itself as a de facto “default” instrument to use in contemporary ensemble music. So if you are writing a piece which will be performed along with other works in a concert , chances are that the trumpet player will already have their C trumpet there.

Moving on to the range. As you probably already know, there is a small difference: the lowest note on a C trumpet without bending or pedals will be the low F♯ (or F natural, if we stretch the 3rd valve slide all the way out); whereas the Bb trumpet will go a whole tone lower (E/Eb), so if those two additional notes mean a lot to your piece, that would be one of the valid reasons to opt for the Bb trumpet. Consequently there is also a difference in the ranges of possible harmonic series (for split-tones, air-sounds etc.). The C trumpet will NOT have the harmonic series over C♯, D, Eb and E; with the Bb trumpet you will gain Eb and E while losing C and B. So this might be something to keep in mind for all the spectralists and post-spectralists out there. Every harmonic series on a same instrument would only be possible with the 4th-valve, however those are unfortunately rarely used these days.

As for the high register, the C trumpet doesn’t go any higher than the Bb, but it might be more precise (less prone to missed notes), especially in the upper part of the second octave, and around the concert high C. Above the high C it doesn’t matter very much; if you aim for precision in that register, you’re better off with the piccolo trumpet (which BTW also doesn’t go any higher than the large trumpets; but the improvement in precision is significant)

6: THE HARMONIC "ARPEGGIO"

Here are a few basic tips about the perceived harmonic arpeggio, which is usually one of the most popular “items on the menu” every time I give presentations of extended techniques to young composers. I saw this technique used a couple of times in an ensemble, mostly wrongly; so maybe it’s a good idea to give a short explanation.

In fact, this is not even a technique, it’s more of a trick we play on the listener, creating the acoustic situation which makes it possible to perceive the natural harmonics that exist in the trumpet sound.

The first prerequisite for this to work is near-absolute silence; so, if it’s not a solo, other instruments should be at their minimum volume. We are using the wa-wa effect, so we need a type of mute that can make accurate changes between different openings. Plunger or bare hand are pretty sloppy at this, wa-wa mute is much better; so is the mellow-wah (a very nice mix between a cup and a wawa, which I wish was used more broadly).

What we are doing is basically opening and closing the mute, not gradually but in measured steps, so that a new harmonic appears with every step.

Obviously, the lower the pitch the easier it is to perceive the harmonics. When playing the lowest note (F on a Bb trumpet, concert Eb) you can perceive the harmonics up until the 8th partial; as you go up, the higher partials will gradually disappear, so that around the middle G you can only hear up to the 5th partial (or maybe this is just me pushing 40 and slowly getting deaf; I’ll have to test this on my kids sometime).

Unfortunately this doesn’t seem to work on pedal tones, so you need to stay within the regular register. By pedal tones I mean the true pedals (under the imaginary fundamental). If a player is able to bend down from the regular register and play the notes between low C♯ and F with a relative stability, that would actually be an ideal register to use for this purpose. The 4th-valve would be perfect here as well; I really don’t know why we don’t use them more often.

Here are a few basic tips about the perceived harmonic arpeggio, which is usually one of the most popular “items on the menu” every time I give presentations of extended techniques to young composers. I saw this technique used a couple of times in an ensemble, mostly wrongly; so maybe it’s a good idea to give a short explanation.

In fact, this is not even a technique, it’s more of a trick we play on the listener, creating the acoustic situation which makes it possible to perceive the natural harmonics that exist in the trumpet sound.

The first prerequisite for this to work is near-absolute silence; so, if it’s not a solo, other instruments should be at their minimum volume. We are using the wa-wa effect, so we need a type of mute that can make accurate changes between different openings. Plunger or bare hand are pretty sloppy at this, wa-wa mute is much better; so is the mellow-wah (a very nice mix between a cup and a wawa, which I wish was used more broadly).

What we are doing is basically opening and closing the mute, not gradually but in measured steps, so that a new harmonic appears with every step.

Obviously, the lower the pitch the easier it is to perceive the harmonics. When playing the lowest note (F on a Bb trumpet, concert Eb) you can perceive the harmonics up until the 8th partial; as you go up, the higher partials will gradually disappear, so that around the middle G you can only hear up to the 5th partial (or maybe this is just me pushing 40 and slowly getting deaf; I’ll have to test this on my kids sometime).

Unfortunately this doesn’t seem to work on pedal tones, so you need to stay within the regular register. By pedal tones I mean the true pedals (under the imaginary fundamental). If a player is able to bend down from the regular register and play the notes between low C♯ and F with a relative stability, that would actually be an ideal register to use for this purpose. The 4th-valve would be perfect here as well; I really don’t know why we don’t use them more often.

7: WATCH OUT FOR THE "BETA-PHASE" EXTENDED TECHNIQUES

Extended techniques for trumpet are constantly developing, in the contemporary music scene as well as in the free improvisation. When you are writing specifically for an advanced trumpeter, they may have been working on a new sound that only they can make, and it may seem very exciting to base the piece around that fresh sound or a new technique that no one has used before.

For example, I have found a way to stiffen my lower jaw and make it tremble on demand; combined with the split-tone technique it can create a sort of a quick tremolo between the two adjacent pairs of split-tones, which can sound pretty awesome. Some of my colleagues and mentors have had their own tricks up their sleeves: my former teacher William Forman had a wonderful “slow flutter” technique that I was hopelessly unable to mimic; Valentin Garvie has become very proficient in playing two trumpets at once; Sava Stoianov has developed an extremely airy sound which is versatile in many dynamics and registers and almost renders obsolete most of the things I wrote above about “half-air half sound”. These are all amazing techniques and sound extremely convincing when you hear them played by their “creators”; and you will surely be immediately inspired to incorporate these sounds in your piece. The disappointing part comes when the piece is performed again, and there is another trumpet player, most likely also great in their own way, but simply can't come even close to reproducing that beautiful sound.

There are another kinds of techniques which won't always work the same way, the half-valve technique comes to mind. It can sound great one day, and absolutely awful the next day. Many half-valve positions will have its own harmonic series, and yes, you can also do split-tones on any two adjacent harmonics in that series; and yes, this can sound pretty amazing (especially in combination with the above mentioned ghost tones). The problem is that tomorrow you will press the valve a ¼ millimeter less or bend your lip at a slightly different angle, and the nice split-tone will be lost forever.

I believe all of these things are “work in progress” and there will come a time when you can casually write them in the score and every player will be able to reproduce them (just like we can today with basic things like flutter tongue and valve-tremolo)

Until that time comes, be careful. I'm not telling you to avoid using any new and untested techniques because as composers you can (and should!) play a role in this progress; just be aware and lower your expectations every time you work with a trumpet player different than the one you wrote the piece for.

Extended techniques for trumpet are constantly developing, in the contemporary music scene as well as in the free improvisation. When you are writing specifically for an advanced trumpeter, they may have been working on a new sound that only they can make, and it may seem very exciting to base the piece around that fresh sound or a new technique that no one has used before.

For example, I have found a way to stiffen my lower jaw and make it tremble on demand; combined with the split-tone technique it can create a sort of a quick tremolo between the two adjacent pairs of split-tones, which can sound pretty awesome. Some of my colleagues and mentors have had their own tricks up their sleeves: my former teacher William Forman had a wonderful “slow flutter” technique that I was hopelessly unable to mimic; Valentin Garvie has become very proficient in playing two trumpets at once; Sava Stoianov has developed an extremely airy sound which is versatile in many dynamics and registers and almost renders obsolete most of the things I wrote above about “half-air half sound”. These are all amazing techniques and sound extremely convincing when you hear them played by their “creators”; and you will surely be immediately inspired to incorporate these sounds in your piece. The disappointing part comes when the piece is performed again, and there is another trumpet player, most likely also great in their own way, but simply can't come even close to reproducing that beautiful sound.

There are another kinds of techniques which won't always work the same way, the half-valve technique comes to mind. It can sound great one day, and absolutely awful the next day. Many half-valve positions will have its own harmonic series, and yes, you can also do split-tones on any two adjacent harmonics in that series; and yes, this can sound pretty amazing (especially in combination with the above mentioned ghost tones). The problem is that tomorrow you will press the valve a ¼ millimeter less or bend your lip at a slightly different angle, and the nice split-tone will be lost forever.

I believe all of these things are “work in progress” and there will come a time when you can casually write them in the score and every player will be able to reproduce them (just like we can today with basic things like flutter tongue and valve-tremolo)

Until that time comes, be careful. I'm not telling you to avoid using any new and untested techniques because as composers you can (and should!) play a role in this progress; just be aware and lower your expectations every time you work with a trumpet player different than the one you wrote the piece for.

LAST BUT NOT LEAST:

Most of what I get asked about by composers at workshops and read-through sessions are the special effects, extended techniques, tricks, gimmicks, noises etc. They are all really interesting but we shouldn’t forget the vast possibilities you can achieve with a normal trumpet sound.

Let me make a small analogy: as a passionate hobby-cook with a particular affection for Indian and Chinese food; I have dozens (maybe hundreds) of spices and condiments available at my pantry at all times. It is amazing getting to know each one, and finding out creative ways of including them in your dishes.

However: you can’t just put a bunch of spices in a pot and call it a meal; every good meal consists mostly of the boring everyday ingredients, things like salt, sugar, onions, garlic, meat, cabbage, tomato, potato, lemon etc. Those are all needed to establish the balance of the basic tastes, after which you can make it stand out with other special and unusual additions.

Please keep this in mind while composing. The pieces that survive the test of time are those that have some substance and are more than just spices. I don't think I'm being old fashioned or reactionary here, it’s just that after 20 years in this business and over 500 contemporary pieces played I’ve had plenty of opportunity to see what works and what doesn’t.

When I get a bit more technology-savvy, I would like to make a post and showcase some of the most “successful” modern compositions for trumpet (solo pieces and trumpet parts from ensemble and orchestra literature), from easy to borderline-unplayable, and have a discussion about what it is that makes them successful, and why we enjoy playing them even if they are sometimes killing us.

PS

Now that I finished writing this article, I'm slowly beginning to realize that it really should have been a video... Too many vague explanations for what could have been easily demonstrated in practice. Sorry about that, I hope it has been at least somewhat useful.

Most of what I get asked about by composers at workshops and read-through sessions are the special effects, extended techniques, tricks, gimmicks, noises etc. They are all really interesting but we shouldn’t forget the vast possibilities you can achieve with a normal trumpet sound.

Let me make a small analogy: as a passionate hobby-cook with a particular affection for Indian and Chinese food; I have dozens (maybe hundreds) of spices and condiments available at my pantry at all times. It is amazing getting to know each one, and finding out creative ways of including them in your dishes.

However: you can’t just put a bunch of spices in a pot and call it a meal; every good meal consists mostly of the boring everyday ingredients, things like salt, sugar, onions, garlic, meat, cabbage, tomato, potato, lemon etc. Those are all needed to establish the balance of the basic tastes, after which you can make it stand out with other special and unusual additions.

Please keep this in mind while composing. The pieces that survive the test of time are those that have some substance and are more than just spices. I don't think I'm being old fashioned or reactionary here, it’s just that after 20 years in this business and over 500 contemporary pieces played I’ve had plenty of opportunity to see what works and what doesn’t.

When I get a bit more technology-savvy, I would like to make a post and showcase some of the most “successful” modern compositions for trumpet (solo pieces and trumpet parts from ensemble and orchestra literature), from easy to borderline-unplayable, and have a discussion about what it is that makes them successful, and why we enjoy playing them even if they are sometimes killing us.

PS

Now that I finished writing this article, I'm slowly beginning to realize that it really should have been a video... Too many vague explanations for what could have been easily demonstrated in practice. Sorry about that, I hope it has been at least somewhat useful.