JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL: TRUMPET CONCERTO IN E

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

The Hummel concerto is such a seminal work for our instrument (some would call it the “Mozart concerto we never had”), that it’s played virtually everywhere in the world. It is performed in concert halls, by professional players and acclaimed soloists with orchestra accompaniment on modern and period instruments; but still, the vast majority of Hummel performances take place within the music schools, conservatories, entrance exams, final exams, competitions etc. There are thousands of trumpet students and young players out there on any given day who are facing this technically and musically challenging concerto; sometimes with an appropriate musical mentorship, but often without. Unfortunately there are a lot of outdated ideas still floating around, resulting in many flat, uninspired performances and a lack of appreciation for this beautiful piece of music (I've rarely met a student who would list this concerto among their favorites).

It does seem that we'd benefit from casting a fresh look at the way Hummel is understood, performed and taught, and while I don’t find it possible nor appropriate to cover any real and essential questions about the musical interpretation in a form of a simple blog post, at least not in the way I would approach it in an actual face-to-face lesson (as John Cage accurately puts it: “writing about music is like dancing about architecture”), I’d like to share my two cents on some specific stylistic matters and questions that often come up during the lessons and masterclasses.

It does seem that we'd benefit from casting a fresh look at the way Hummel is understood, performed and taught, and while I don’t find it possible nor appropriate to cover any real and essential questions about the musical interpretation in a form of a simple blog post, at least not in the way I would approach it in an actual face-to-face lesson (as John Cage accurately puts it: “writing about music is like dancing about architecture”), I’d like to share my two cents on some specific stylistic matters and questions that often come up during the lessons and masterclasses.

Disclaimer: I don’t claim to be any sort of “authority” on the classical style and you may very well disagree with most of what I write, however I am at least hoping to encourage other trumpet players to give this some more thought. Who knows, maybe disagreeing with me will help you define how you actually feel about it.

1: TRILLS

The eternal question: do I begin the trill with the upper or with the lower note? I don’t think there is a firm rule that we have to follow, however there is some information available to us which can definitely help.

It is common knowledge that there was a rather gradual shift in taste (from “upper note first” towards “lower note first”) starting around the end of the 18th century. There is a direct quote from Hummel himself, taken from his piano method written in 1828 (in my sloppy translation from the old German):

“…When it comes to the trills, one has stuck with the old habit, and begins the trill with the upper neighbor. This is probably based on some early ground rules designed mainly for the singers, which were later taken over by the instrumentalists…” “…therefore the trill should always begin from the main note (unless specified otherwise)...”

For many people this would enough evidence to convince them to begin all Hummel trills from the lower (main) note. However, I would like to point out several arguments why this might not be as easy a decision as it seems.

First of all, Hummel was a pianist and one of the most respected authorities of his time when it comes to piano; still a relatively new instrument which plays by its own rules in many ways, especially when it comes to embellishments. In the quote he is mainly referring to the contemporary appropriate style of piano playing. The trumpet concerto, however, was written in 1803 when he was much younger (a lot can change in 25 years: today is not 2028, it’s only 2022, but in the contemporary music scene there was a very clear change in the aesthetics compared to the 2003, I may write some more about that in other posts). Furthermore, the trumpet concerto is clearly stylistically influenced by several works of Mozart (Hummel’s childhood mentor), who had already died 12 years prior; creating an even larger time barrier. The most notable similarity can be observed between the 1st movement opening themes of the trumpet concerto and Mozart's 35th Symphony in D-major aka the "Haffner Symphony", premiered in 1783 (by the way, this "lineage" can be traced via the Haffner Symphony further back to Mozart's own mentor, J.C. Bach, and the beginning of his Symphony Op.18 No.1 in Eb-Major). Finally, applying the “vocal rules” (however outdated they may be) to a wind instrument might make more sense than applying them to a mechanical one, such as the piano.

Just for fun, we can take a look at the trill treatment in some of his later music, particularly the piano concertos. An especially interesting piece for us would be the 4th piano concerto in E-major from 1814. Being in the same key, and starting the solo part with almost the same motif, it also offers some other clear nods and similarities to the trumpet concerto (such as the characteristic 4-bar bridge before the first entrance of the soloist; as well as the same sudden modulation into C-major during the first tutti after the exposition). Still, the general style of this piece is already much more mature and complex and the cadential trills are barely present, even though it is only 10 years older. If we check the 5th Concerto from 1827 (written around the same time as the quote from the piano method) we can still recognize the early (Mozart influenced) style in the orchestra, but the solo material has already gone so far ahead in time that it may sound closer to Chopin than to our poor old trumpet concerto. All in all, this isn’t telling us very much. The trills do appear from time to time, but the preceding melodic line is always led in such a manner to make it obvious they should start from the lower note; which leads me to my main argument:

The melody usually already tells us what to do.

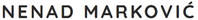

If we come back to the trumpet concerto, and look at what happens right before the final trill of the 1st movement, the very last 16th note before the trill (F♯) is the subsequent main note of the trill. Wouldn’t it be a bit awkward breaking up the line, right at its climax, and having to re-attack the same note (if we were starting from below)? Let's stop the music right at the first note of the trill, and see which melody makes more sense:

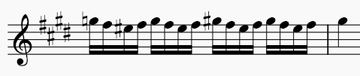

Another clear example would be m.27 of the 2nd movement.

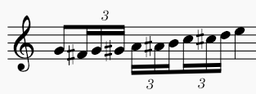

Also: what would be the point in restarting the trill in m. 230 of the 3rd movement if you don’t place some emphasis on the restart? Trying to create that emphasis while starting from the main note seems counterintuitive to me. The one obvious exception is the part right before that; with the long, chromatically ascending trill, from m. 222 onward. This is clearly not a cadential trill and serves a completely different function; so I believe all of those should start from below, to give us a chance to understand what’s going on with the harmony.

|

Funnily enough, there is a quite similar situation in the 4th piano concerto at the very end of the 1st movement: the trills are ascending chromatically, beginning from the lower note, reaching (and resting) on the F♯ trill (just like the trumpet concerto). However, this time instead of restarting the trill in the last two measures, Hummel opts for a much more effective ending: a jump to the high B followed by a quick diatonic nosedive of 4 1/2 octaves into the low E (yes, it is kind of tempting to try and incorporate a slower and shorter version of this stunt into our piece. On your own risk, of course). |

On the flip side: the final trill of the exposition (m. 145 in the 1st mvt.) isn’t preceded by a melodic line, but with those 4 bouncing notes of the B-major triad, which are looking eager to bounce straight into the C♯ (as there is no melodic line, there is no need to create the harmonic suspension; and also it would mean repeating the D♯ which is always a bit clumsy, as I already stated above).

For me, this would be a stronger argument than the argument of consistency with the later trills; so I would in fact begin this trill from below. Similarly, the melody in the m.81 (sort of a micro Haydn-quote) is also going to make more sense and be more recognizable if the trill is played from below.

My final verdict (after considering all the arguments and counter-arguments):

1st movement: m. 81 and 145 from below, m. 297 from above

2nd movement: everything from above, as long as it’s even an actual trill (see next chapter)

3rd movement: m.222 through (and including) m. 226 from below, m. 230 from above

PS

And please (I can't even remember how many times I've had to say this in a lesson): if the trill has those two termination notes written at the end, please follow through and don't stop until you reach the two notes. If you have trouble connecting them to the rest of the trill, begin by practicing the trill in the steady 1/16th notes (if it begins with the upper note), or 1 triplet + 3 groups of 1/16 notes (if it begins with the lower). Add the acceleration element only after the two last notes are well connected to the rest of the trill.

Arban is your friend, consult the trill section from the book and you'll be fine.

My final verdict (after considering all the arguments and counter-arguments):

1st movement: m. 81 and 145 from below, m. 297 from above

2nd movement: everything from above, as long as it’s even an actual trill (see next chapter)

3rd movement: m.222 through (and including) m. 226 from below, m. 230 from above

PS

And please (I can't even remember how many times I've had to say this in a lesson): if the trill has those two termination notes written at the end, please follow through and don't stop until you reach the two notes. If you have trouble connecting them to the rest of the trill, begin by practicing the trill in the steady 1/16th notes (if it begins with the upper note), or 1 triplet + 3 groups of 1/16 notes (if it begins with the lower). Add the acceleration element only after the two last notes are well connected to the rest of the trill.

Arban is your friend, consult the trill section from the book and you'll be fine.

2: FLATTEMENTS

So, we’ve dealt with the trills, but what about that wavy line that sometimes shows up without the “tr” marking? All newer editions agree that this was not a coincidence but a marking for the “flattement” or “sweetening”, which is an effect that a lot of woodwind instruments were using at the time, somewhat similar to the modern day bisbigliando. This is a demonstration of a flattement on a baroque recorder. They were also standard on most other keyed woodwind instruments which made them an option for the keyed trumpet as well. There they were produced by alternating two positions of the same pitch, sort of like a predecessor to the modern day valve-tremolo (one tone would usually be more “airy” and distorted then the other, but the pitch would stay relatively stable, making a clear distinction from the trill). In the Hummel concerto these markings appear in several places: 2nd movement, m.4 and 47 as well as m. 218 of the 3rd movement. Just to have a clear picture of how a flattement sounds on a keyed trumpet, here are the 2nd and 3rd movement of my favorite commercially available recording on the instrument, by my teacher prof. Reinhold Friedrich

So, what should we do with the modern trumpet?

If we make a trill, there will be no distinction with all other trills in the piece. Furthermore, the trill may sound a bit aggressive in the delicate beginning of the 2nd movement, and will interrupt the buildup from m.216 of the 3rd movement (steady tone>flattement>trill). What most newer editions recommend instead is to use an “expressive vibrato” in place of a flattement. However, whether or not this vibrato will even be noticeable at all depends most of all on what your general stance on continuous vibrato is. The continuous vibrato (or “the MSG of music” as Bruce Haynes calls it in his wonderful book “The end of early music”), was already becoming a subject of debate in the early XIX century. From what I can gather, the scholars were mostly still advising against it, but a lot of the players were already using it nonetheless. Even though the continuous left hand shake the string players use didn’t become the norm until several decades later, for wind instruments and singers it would have been a pretty common practice to let the sound naturally vibrate as it’s opening up in a slow crescendo, such as the case in the beginning of the 2nd mvt. So, unless you either force yourself to play the entire rest of the 2nd movement completely flat and non-vibrato, or make a particularly grotesque vibrato at the wavy lines, this clearly notated embellishment effect will not be perceivable as such, but just as regular musicianship.

Because of all this, I propose a third solution, as I believe an actual flattement would be the right choice for the wavy lines, even if we play on a modern trumpet. We no longer have keys (except for the water key, which I guess we could technically use to make a flattement with, but it’s usually wet and will make an ugly hissing noise; while also being visually distracting for the audience). What we do have, however, are our 3 valves, which are very versatile and full of surprises. So, I came up with this “1mm trill” to mimic the flattement. Basically, it’s a trill but I’m lifting the finger just enough that the timbre changes but not enough for the pitch to slip away, so: around 1 mm. It works like a charm on some notes, it’s slightly more awkward on others, but it is always doable unless the note is in an open position (in which case your better option is to use an alternative fingering, as I found the trilling down from the open position to be somewhat harder to control).

Here's a quick demonstration Marina and I recorded at the Academy; the beginning and the middle part from the 2nd mvt as well as the buildup from the 3rd mvt (just for fun I also added the aforementioned alternative ending from the 4th piano concerto)

So, we’ve dealt with the trills, but what about that wavy line that sometimes shows up without the “tr” marking? All newer editions agree that this was not a coincidence but a marking for the “flattement” or “sweetening”, which is an effect that a lot of woodwind instruments were using at the time, somewhat similar to the modern day bisbigliando. This is a demonstration of a flattement on a baroque recorder. They were also standard on most other keyed woodwind instruments which made them an option for the keyed trumpet as well. There they were produced by alternating two positions of the same pitch, sort of like a predecessor to the modern day valve-tremolo (one tone would usually be more “airy” and distorted then the other, but the pitch would stay relatively stable, making a clear distinction from the trill). In the Hummel concerto these markings appear in several places: 2nd movement, m.4 and 47 as well as m. 218 of the 3rd movement. Just to have a clear picture of how a flattement sounds on a keyed trumpet, here are the 2nd and 3rd movement of my favorite commercially available recording on the instrument, by my teacher prof. Reinhold Friedrich

So, what should we do with the modern trumpet?

If we make a trill, there will be no distinction with all other trills in the piece. Furthermore, the trill may sound a bit aggressive in the delicate beginning of the 2nd movement, and will interrupt the buildup from m.216 of the 3rd movement (steady tone>flattement>trill). What most newer editions recommend instead is to use an “expressive vibrato” in place of a flattement. However, whether or not this vibrato will even be noticeable at all depends most of all on what your general stance on continuous vibrato is. The continuous vibrato (or “the MSG of music” as Bruce Haynes calls it in his wonderful book “The end of early music”), was already becoming a subject of debate in the early XIX century. From what I can gather, the scholars were mostly still advising against it, but a lot of the players were already using it nonetheless. Even though the continuous left hand shake the string players use didn’t become the norm until several decades later, for wind instruments and singers it would have been a pretty common practice to let the sound naturally vibrate as it’s opening up in a slow crescendo, such as the case in the beginning of the 2nd mvt. So, unless you either force yourself to play the entire rest of the 2nd movement completely flat and non-vibrato, or make a particularly grotesque vibrato at the wavy lines, this clearly notated embellishment effect will not be perceivable as such, but just as regular musicianship.

Because of all this, I propose a third solution, as I believe an actual flattement would be the right choice for the wavy lines, even if we play on a modern trumpet. We no longer have keys (except for the water key, which I guess we could technically use to make a flattement with, but it’s usually wet and will make an ugly hissing noise; while also being visually distracting for the audience). What we do have, however, are our 3 valves, which are very versatile and full of surprises. So, I came up with this “1mm trill” to mimic the flattement. Basically, it’s a trill but I’m lifting the finger just enough that the timbre changes but not enough for the pitch to slip away, so: around 1 mm. It works like a charm on some notes, it’s slightly more awkward on others, but it is always doable unless the note is in an open position (in which case your better option is to use an alternative fingering, as I found the trilling down from the open position to be somewhat harder to control).

Here's a quick demonstration Marina and I recorded at the Academy; the beginning and the middle part from the 2nd mvt as well as the buildup from the 3rd mvt (just for fun I also added the aforementioned alternative ending from the 4th piano concerto)

I tried out the flattements a couple of times in a concert, I teach them to my students as well as in masterclasses and in a way I really believe this comes pretty close to the original intent. It will seem extravagant at the first listening, but after you've heard it a few times in the context it will actually blend quite nicely and won't take away too much attention from the music (a problem we are much more likely to have with the pedal tone in 1st mvt, m.245; but that’s a different subject)

3: TEMPO

I think we can all agree that there’s nothing more tedious than when the 1st movement of Hummel is played too slow (which I’d say would be anywhere under 120 bpm). The “allegro con spirito” quickly turns into its opposite (I guess that would make it “triste, senza spirito”), and I’ve surely had my fair share of moments sitting in competition jurys, listening to the tortoise-paced 1st movement and wishing I was literally anywhere else.

But how fast should it be then? At what speed does the "spirito" appear?

There is actually an entire doctoral dissertation available online where most existing recordings of the 1st movement were analyzed beat by beat, calculating the average tempo of every performance as well as the tempo deviations throughout the performance. Although the amplitude goes from 122 to 138 bpm, most trumpet players hover somewhere between 132 and 136 bpm. But if we compare this to the various recordings of the aforementioned 1st mvt. of the Haffner symphony by Mozart; we'll find that the tempo goes all the way up to 152-154 bpm in some cases.

In my opinion, both of these movements by Hummel and Mozart are very flamboyant, high energy works that can only benefit from being pushed a few bpm’s higher. The lyrical bits (such as m. 90 or m. 229) are set sparsely enough, so there is no real danger of them feeling rushed. So if a player can pull it off to keep the technical passages clean, I’d say my “tempo giusto” could easily be placed somewhere within 136-144 bpm.

The 3rd movement however is an entirely different story.

I feel that a lot of the older recordings (and sadly some current ones too) are indeed feeling very rushed and mechanical, showing off the virtuosity for the sake of virtuosity. I see the third movement more as a very relaxed and restrained ballet, and definitely not as a gallop. Try imagining that you should be able to conduct this movement in quarter notes without breaking out in sweat.

Taking it easy with the tempo will allow you to recognize the melodic lines in the 16-note passages of the first part; you ‘ll be able to switch to simple tonguing, maybe even “sit” a bit on the first note in a group of four. Particularly notable is the third part: Hummel completely gives up on the main theme of the rondo and instead introduces a direct quote from the Cherubini opera "Les deux journées", mashed up with the expanded ornament quotes from the Haydn Trumpet Concerto. As the anecdote goes, this opera was very popular in Vienna for months before the Hummel Concerto was premiered, and Anton Weidinger (the keyed-trumpet pioneer who commissioned both Haydn and Hummel concertos) was a big fan of the opera and was upset that he couldn’t play it, so Hummel wrote this theme into the concerto as sort of a Christmas present for Weidinger. The opera was written in E-major, which may or may not have influenced the decision to modify the tuning of the Eb instrument previously used for Haydn Concerto. If this is true, it would mean a whole lot of effort was put in so that the Cherubini quote is instantly recognizable and presented as true as possible to the original.

Now, this is a recording of the bit from the opera which is directly quoted (the theme is best heard around 5:40, when the singers finish)

Of course I’m not suggesting we should play it THAT slowly (it's something like 160 bpm on this recording, but the note values are augmented, since Cherubini scored the piece in 4/4 Allegro; meaning that the equivalent Hummel tempo would be 80 bpm, which is obviously unacceptable). We could however still make some compromise here. I quite like the tempo Reinhold Friedrich took in the keyed-trumpet recording posted above. I believe this is around 116 bpm. I would recommend hovering around 120bpm on a modern trumpet as well; it’s very nice to have the difficult passages such as m. 53 or m. 87 still seem calm and elegant instead of "show-offy" and aggressive.

As for the second movement, I think this music is more forgiving and I certainly don't remember ever hearing it played in a tempo I didn't like; so we can move on to the next chapter.

I think we can all agree that there’s nothing more tedious than when the 1st movement of Hummel is played too slow (which I’d say would be anywhere under 120 bpm). The “allegro con spirito” quickly turns into its opposite (I guess that would make it “triste, senza spirito”), and I’ve surely had my fair share of moments sitting in competition jurys, listening to the tortoise-paced 1st movement and wishing I was literally anywhere else.

But how fast should it be then? At what speed does the "spirito" appear?

There is actually an entire doctoral dissertation available online where most existing recordings of the 1st movement were analyzed beat by beat, calculating the average tempo of every performance as well as the tempo deviations throughout the performance. Although the amplitude goes from 122 to 138 bpm, most trumpet players hover somewhere between 132 and 136 bpm. But if we compare this to the various recordings of the aforementioned 1st mvt. of the Haffner symphony by Mozart; we'll find that the tempo goes all the way up to 152-154 bpm in some cases.

In my opinion, both of these movements by Hummel and Mozart are very flamboyant, high energy works that can only benefit from being pushed a few bpm’s higher. The lyrical bits (such as m. 90 or m. 229) are set sparsely enough, so there is no real danger of them feeling rushed. So if a player can pull it off to keep the technical passages clean, I’d say my “tempo giusto” could easily be placed somewhere within 136-144 bpm.

The 3rd movement however is an entirely different story.

I feel that a lot of the older recordings (and sadly some current ones too) are indeed feeling very rushed and mechanical, showing off the virtuosity for the sake of virtuosity. I see the third movement more as a very relaxed and restrained ballet, and definitely not as a gallop. Try imagining that you should be able to conduct this movement in quarter notes without breaking out in sweat.

Taking it easy with the tempo will allow you to recognize the melodic lines in the 16-note passages of the first part; you ‘ll be able to switch to simple tonguing, maybe even “sit” a bit on the first note in a group of four. Particularly notable is the third part: Hummel completely gives up on the main theme of the rondo and instead introduces a direct quote from the Cherubini opera "Les deux journées", mashed up with the expanded ornament quotes from the Haydn Trumpet Concerto. As the anecdote goes, this opera was very popular in Vienna for months before the Hummel Concerto was premiered, and Anton Weidinger (the keyed-trumpet pioneer who commissioned both Haydn and Hummel concertos) was a big fan of the opera and was upset that he couldn’t play it, so Hummel wrote this theme into the concerto as sort of a Christmas present for Weidinger. The opera was written in E-major, which may or may not have influenced the decision to modify the tuning of the Eb instrument previously used for Haydn Concerto. If this is true, it would mean a whole lot of effort was put in so that the Cherubini quote is instantly recognizable and presented as true as possible to the original.

Now, this is a recording of the bit from the opera which is directly quoted (the theme is best heard around 5:40, when the singers finish)

Of course I’m not suggesting we should play it THAT slowly (it's something like 160 bpm on this recording, but the note values are augmented, since Cherubini scored the piece in 4/4 Allegro; meaning that the equivalent Hummel tempo would be 80 bpm, which is obviously unacceptable). We could however still make some compromise here. I quite like the tempo Reinhold Friedrich took in the keyed-trumpet recording posted above. I believe this is around 116 bpm. I would recommend hovering around 120bpm on a modern trumpet as well; it’s very nice to have the difficult passages such as m. 53 or m. 87 still seem calm and elegant instead of "show-offy" and aggressive.

As for the second movement, I think this music is more forgiving and I certainly don't remember ever hearing it played in a tempo I didn't like; so we can move on to the next chapter.

4. MISCELLANEOUS

(Just some quick, specific questions that don’t merit a standalone chapter)

-Is the last trill in the 2nd mvt a semitone or a whole tone trill?

Sadly, it’s clearly a semitone trill. Many people play the whole tone trill and the augmented fourth sounds pretty amazing to be honest; I’ve had it in my ears and played like that for many years (don’t judge me if I still do it from time to time). Unfortunately, I can’t think of any musical justification to back this up. Sometimes the wrong thing is fun, but it doesn’t make it less wrong.

-Should I play the Eb-major or the E-major version

Eb-major is fine for young players, and is actually one of my favorite entrance-exam pieces; but for any solo appearance, recitals, competitions, especially if you're playing with the orchestra, the E-major version is the only correct option, it’s the original.

Yes, I know that very few people own an E-trumpet, and even fewer people own an E-trumpet which can actually play in tune; but the piece is perfectly playable on a C-trumpet (the main key is the E-major, but it often ventures into C-major and a-minor; so it’s really not that difficult. Also your piano accompanist will love you for not having to put up with tons of accidentals). The only really tricky part on a C-trumpet is the grupetto-extravaganza in the 3rd movement Haydn-quote (m. 194), but as I wrote above, there really is no reason to play the 3rd movement all that fast anyway, so in a more relaxed tempo you’ll manage just fine.

-If I do play the Eb major version, should I play it on a Bb or Eb trumpet?

No reason to get an Eb trumpet just for this, if you ask me. I’m not a very big fan of the color anyway. If you’re a beginner, you can play the Eb-major version on a Bb trumpet you already have; otherwise: see above.

-What about the cadenza?

Well, in the score there is no mention of the cadenza and I was always taught that while you can interpret some things more freely, you shouldn’t downright invent stuff; so I never played the cadenza in Hummel. But, I guess, if you were going to do it, that ending of the 1st movement (before the pizzicato) does kind of offer itself as a pretty appropriate place. That’s where Maurice André plays it, and I no longer think it would be the biggest sin in the world. I might even play a cadenza of my own there one day…

(Just some quick, specific questions that don’t merit a standalone chapter)

-Is the last trill in the 2nd mvt a semitone or a whole tone trill?

Sadly, it’s clearly a semitone trill. Many people play the whole tone trill and the augmented fourth sounds pretty amazing to be honest; I’ve had it in my ears and played like that for many years (don’t judge me if I still do it from time to time). Unfortunately, I can’t think of any musical justification to back this up. Sometimes the wrong thing is fun, but it doesn’t make it less wrong.

-Should I play the Eb-major or the E-major version

Eb-major is fine for young players, and is actually one of my favorite entrance-exam pieces; but for any solo appearance, recitals, competitions, especially if you're playing with the orchestra, the E-major version is the only correct option, it’s the original.

Yes, I know that very few people own an E-trumpet, and even fewer people own an E-trumpet which can actually play in tune; but the piece is perfectly playable on a C-trumpet (the main key is the E-major, but it often ventures into C-major and a-minor; so it’s really not that difficult. Also your piano accompanist will love you for not having to put up with tons of accidentals). The only really tricky part on a C-trumpet is the grupetto-extravaganza in the 3rd movement Haydn-quote (m. 194), but as I wrote above, there really is no reason to play the 3rd movement all that fast anyway, so in a more relaxed tempo you’ll manage just fine.

-If I do play the Eb major version, should I play it on a Bb or Eb trumpet?

No reason to get an Eb trumpet just for this, if you ask me. I’m not a very big fan of the color anyway. If you’re a beginner, you can play the Eb-major version on a Bb trumpet you already have; otherwise: see above.

-What about the cadenza?

Well, in the score there is no mention of the cadenza and I was always taught that while you can interpret some things more freely, you shouldn’t downright invent stuff; so I never played the cadenza in Hummel. But, I guess, if you were going to do it, that ending of the 1st movement (before the pizzicato) does kind of offer itself as a pretty appropriate place. That’s where Maurice André plays it, and I no longer think it would be the biggest sin in the world. I might even play a cadenza of my own there one day…

5. WHY BOTHER WITH ALL THIS?

“Historically informed performance” practice (often shortened as “HIP” in various texts, making the people who practice this approach the “hipsters” of classical music, which may be a pretty accurate description) has been around for more than 50 years now. And yet, the more reading I did on the subject the more it seemed to me that this whole approach was welcomed and praised by the musical world for about one day; after which the various forms of reactionary criticism sprung up from all sides; with the discussion often reaching for the (ever so popular) "whataboutism" and hypocrisy fallacies.

While some of the critics' points are valid (yes, we can’t know for sure that the composer meant exactly that; and no, even if we did, we’re not required to obey); I think that HIP is definitely a necessary step forward from the way early music was approached before; which was to play it without any consideration of measures, beat hierarchy, gestural phrasing, groupings and all other micro-structures of the melody; bound only by the aesthetics we carried over from the romantic and neo-romantic music (which is the first historical style that stayed alive and well preserved, helped by the creation of music conservatories and philharmonic societies throughout the world).

This could be one way to summarize the ideal development of the student’s musical idea, where the even the most rigid approach to HIP still plays a beneficial role (my younger readers are welcome to imagine the following table in the form of a “Fancy Winnie the Pooh” meme):

“Historically informed performance” practice (often shortened as “HIP” in various texts, making the people who practice this approach the “hipsters” of classical music, which may be a pretty accurate description) has been around for more than 50 years now. And yet, the more reading I did on the subject the more it seemed to me that this whole approach was welcomed and praised by the musical world for about one day; after which the various forms of reactionary criticism sprung up from all sides; with the discussion often reaching for the (ever so popular) "whataboutism" and hypocrisy fallacies.

While some of the critics' points are valid (yes, we can’t know for sure that the composer meant exactly that; and no, even if we did, we’re not required to obey); I think that HIP is definitely a necessary step forward from the way early music was approached before; which was to play it without any consideration of measures, beat hierarchy, gestural phrasing, groupings and all other micro-structures of the melody; bound only by the aesthetics we carried over from the romantic and neo-romantic music (which is the first historical style that stayed alive and well preserved, helped by the creation of music conservatories and philharmonic societies throughout the world).

This could be one way to summarize the ideal development of the student’s musical idea, where the even the most rigid approach to HIP still plays a beneficial role (my younger readers are welcome to imagine the following table in the form of a “Fancy Winnie the Pooh” meme):

|

PHASE 1

|

“I want to play it like this because one guy in the 70s played it this way, then another guy in the 80s copied him, and then another guy copied that guy, so now that’s just how it’s done, and who am I to question that?”

|

|

PHASE 2

|

“I want to play it like this because a research paper says that this is exactly how they played it 220 years ago, so this is the way it’s supposed to be played, and who am I to question that?”

|

|

PHASE 3

|

“I want to play it like this because I'm beginning to understand the deeper meaning of this music and it’s place within the historical context it was created in; and I’m making my own artistic choices based upon both my visceral instincts and the vast body of existing theoretical research available to me today”

|

Sadly there are still many trumpet players today, even aspiring soloists, who are either stuck in phase 1, or are attempting to bypass phase 2 and jump straight into 3. Playing solely according to your instincts will be neither interesting nor relevant, unless your instincts are based on the musical knowledge which you have acquired consciously and systematically.

It is still possible to impress people with only a good sound production, beautiful timbre and precise attacks; because up until recently these things were exceptionally rare on our instrument; but as the trumpet develops there will be more and more young players who have the “perfect” sound and technique, and they can’t all become superstars and sell albums (unless they’re really pretty). At some point you will need to bring something more to the table if you expect to stand out from the crowd. While there is definitely no such a thing as the “one and only” appropriate tempo, articulation, dynamic etc. there definitely are tempi, articulations and dynamics which facilitate the inner meaning of the music to come across; and if I’m about to buy someone’s recording or pay for the concert ticket, I expect to be offered a nuanced and deliberate interpretation and have my brain just as engaged as my ears.

What does the Hummel Concerto mean to a random person in the audience? Is it a masterpiece? A sublime and nuanced work of late classicism introducing a new instrument to the elite club of (very few) "worthy" solo instruments? Or is it a clumsy, experimental piece by a young composer who'll only reach his full maturity much later with his romantic piano works; a sort of a 1804-New-Years-party "Gebrauchsmusik" which should have been forgotten as soon as the guests woke up the next morning, cured their hangovers and moved on with their lives? Potentially it could be both of these things, and anything in between.

The answer is in our hands.